The Beaver brought paper, portfolio, pens,

And ink in unfailing supplies:

While strange creepy creatures came out of their dens,

And watched them with wondering eyes.

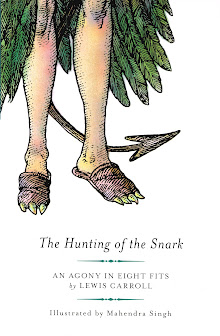

Strange, creepy creatures are the bane of modern life and both Lewis Carroll and myself have seen fit to embellish this crucial stanzel of The Hunting of the Snark with a surfeit of ‘em. Suitably alarmed, the Butcher has darted into a convenient telephone booth and re-emerged in the guise of St. Anthony, the father of Christian monasticism and more to our purposes, a veritable bit of human fly-paper for all manner of hallucinatory things that go bump in the night.

The attentive reader will remember that the very first stanzel of this Snark involved a direct quotation from Mathias Grünewald’s version of St. Anthony, a quotation which involved a fair bit of mirror-work and the cramming of a very hirsute and oddly fey Saint into the sturdy 19th-century country-squire’s boots of the Boots, AKA Charles Darwin. This saint-bashing mania of mine is shared with many other artists; throughout the ages, we picture-folk (or Bildervolk, gesundheit) have mass-produced St. Anthonys by the bucketful. Even Henry Holiday joined in the fun, establishing an Antonine precedent for Fit the Fifth which even the religiously fastidious Lewis Carroll approved!

From whence comes this Antiantonimania? Are Salvador Dali (the Norman Rockwell of Surrealism), Hieronymus Bosch, Feliciens Rops and Gustave Flaubert all victims of a sudden outbreak of religious fervor? Or is it all just an excuse to draw legions of naked women and creepy circus sideshow freaks mobbing a defenseless old man in a desert?

To be sure, there is a certain visual, even Luis Buñuel kind of appeal to such a proposition but nonetheless, dear reader, it’s just not very sporting, is it? The genuinely Christian thing to do is to insist that all these unreal phenomena besetting a very real person are promptly replaced with a new and improved denful of very real phenomena besetting a patently unreal person! The latter personage would be, of course, our Snark, and I’m certain that you, the readers and thus the ultimate — and only! — reality of this poem, will do a splendid job of standing in as the former.

So, that’s all settled, is it? I’ll go and have a nice lie-down while you slip into your new Snark-baiting role. Just study the above drawing very carefully and do whatever Mister Bosch says. He does have an active imagination and if anyone asks you why this is so, hint vaguely that it’s just that Hieronymo's mad againe.