I mentioned then that Moebius went through a clear-line phase before returning to his (cross)hatching habits but I should have been more precise: he went to a relatively orthodox clear-line phase, for he already had a modified clear-line "house" style of his own which he used with great effect, especially in the AG. He had several variations of the style and on page 77 we see an excellent sample of one of them. The first specific rule of this page (always bearing in mind the first Three Rules: keep it black & white, camera-ready and pleasing to the eye) is:

4. Use supple, relatively fast lines to render contour and explanatory texture.

This is the fundamental principle of the clear-line style, as practiced by such masters as Hergé, Joost Swaarte, Ted Benoît, etc. Its commercial appeal is obvious although it has one catch: it requires thorough draftsmanship to execute well. Needless to say, Moebius had no problems in that department and his clear-line, both in the AG and his later “minimalist” phase, was eye-popping.

His hand — never forget the physical testimony of the hand! — moves fast on contour then speeds up and down on detail, lightly varying pressure upon the nib to create swell. The whole page looks all-nib, with some lines twice inked to reinforce the rule of thicker towards the foreground & edges, thinner towards the back and centers.

Even when the smaller lines look mono-width, they are not. Look carefully and you’ll see the ceaseless, minute waxing and waning that a dip pen gives to the line. Inkers who use Rapidographs lose much in line energy, much more than they gain in convenience. They are often forced to keep lines shorter so as to not betray the spindliness of extended passages. The line breathes when one uses a flexible nib, and when the hand is fast and confident, the result is lively to the eye.

Even when the smaller lines look mono-width, they are not. Look carefully and you’ll see the ceaseless, minute waxing and waning that a dip pen gives to the line. Inkers who use Rapidographs lose much in line energy, much more than they gain in convenience. They are often forced to keep lines shorter so as to not betray the spindliness of extended passages. The line breathes when one uses a flexible nib, and when the hand is fast and confident, the result is lively to the eye.

This is a conversational page, talking about shape and texture at a brisk (but not hasty) pace. The pen flirts at times with calligraphy but moderates the ratio of line thickness to white space just enough to avoid the brush & ink corporate American comix look. The latter style, which is often a clear-line style, tends to flex the line severely with mixed results.

The problem with hard-core clear-line, especially black & white clear-line, is that the lack of detail often bores the eye after a while. This is a violation of Rule Three (always make the page attractive to the viewer) but Moebius was a law-abiding inkster. To keep the eye happy, he modifies the clear-line by:

5. Rendering lots of detail with anything but explanatory hatching

There is far more detail rendering here than in any page by Hergé or Benoît. Yes, there is slight hatching to indicate a few shadows but generally, the pen is in a bas-relief mode of thinking. Volumes are indicated by rendering around their outer edges or even leaving them blank and rendering the space behind them to make them pop. The rendering itself is mostly texture and sub-contour and the former is often a sub-species of the latter.

The background of tier 2 is technically brilliant. Note that it's optically registering as a minimal 20-30% on the grey scale, ie., the classic Moebius high-keyed look but sans spotting & shadows. Note also the faces of all the figures in all the panels. Clear-line usually symbolizes faces (at the expense of realistic backgrounds) but Moebius has taken care to make each face spare but precise, using the language of figure drawing, not cartooning. The difference is subtle but essential.

By normal clear-line standards, the entire page — and the backgrounds in particular — is over-inked. But look carefully. All the marks are still contour, they are all explanatory, they are all well integrated into the white. There is no risk of confusing the eye, in fact, the opposite is happening, our eyes are enjoying the visual patterns of obsessive detail because they are firmly grounded in optical reality. Our eye loves realistic contour even more than the convenience of orthodox page navigation — confusion is attractive if it is done just so.

The total effect is a pleasing optical confusion of foreground and background such as we saw on page 36. Rule 5 (which operates to satisfy Rule 3, the satisfaction of the eye) has been further modified to:

5a. Make everything precise and dreamlike at once by maintaining an infinite depth of field through obsessive detailing.

Note also the lettering scheme of the last 2 tiers. The lettering is so muscular and supple (and with a brush, the show-off!) but without balloons the morphology of the writing melts back into the semiotic ooze of marks which spawned it. I guess even the words are not really there, either.

This drive to detail, this French-fried chicken-fat, was one of Moebius' deepest impulses. When he went orthodox clear-line, he also made several statements in print about wanting to shed these obsessions but in the end, he went right back to them. The horror vacui was a basic element of his style, even in clear-line, and style is an expression of personality. Moebius was an honest stylist. The Airtight Garage is a genuine self-performance.

The game of art is the game of personality and obsession and desire. Aesthetic and structural rules encourage the deeply seated, collective human language of picture-making to speak clearly through the trained hand, without useless visual solipsism.

On a more practical level, if you're clear-minded about yourself and your obsessive goals, your style will sort itself it out. Above all, avoid passing fads and short-cuts, they encourage character weaknesses and will literally stunt your growth.

The clear-line style is ancient in commercial illustration, it dates back to Greek vase painting and East Asian block-printing. Let's take a look at one of its first appearances in mass-produced Western commercial book illustration, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Here's several page spreads by an anonymous artist, along with some sharp type-setting by Aldus Manutius, that old slicky-boy of the composing room. Note that all three of the basic rules are in full form here, in both type and ill0s.

This drive to detail, this French-fried chicken-fat, was one of Moebius' deepest impulses. When he went orthodox clear-line, he also made several statements in print about wanting to shed these obsessions but in the end, he went right back to them. The horror vacui was a basic element of his style, even in clear-line, and style is an expression of personality. Moebius was an honest stylist. The Airtight Garage is a genuine self-performance.

The game of art is the game of personality and obsession and desire. Aesthetic and structural rules encourage the deeply seated, collective human language of picture-making to speak clearly through the trained hand, without useless visual solipsism.

On a more practical level, if you're clear-minded about yourself and your obsessive goals, your style will sort itself it out. Above all, avoid passing fads and short-cuts, they encourage character weaknesses and will literally stunt your growth.

The clear-line style is ancient in commercial illustration, it dates back to Greek vase painting and East Asian block-printing. Let's take a look at one of its first appearances in mass-produced Western commercial book illustration, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Here's several page spreads by an anonymous artist, along with some sharp type-setting by Aldus Manutius, that old slicky-boy of the composing room. Note that all three of the basic rules are in full form here, in both type and ill0s.

The clear-line of these illos is not as over-rendered as Moebius' baroque variations but it is equally effective. The general aim is still the same: dazzle the reader with a stripped down but compelling approximation of optical reality. There's more about the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili here and guess what? It was constructed according to various obscure constraints of a symbolic and allegorical nature, rather like The Garage.

Constraints and rules! They are the inker's friends, not their chains! Accept the hermetically sealed confines of your own airtight garage and feed your head!

(I tried to post a comment but it sort of disappeared).

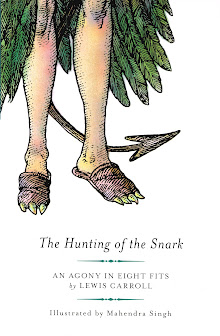

ReplyDeleteHello Mahendra,

thanks for this series: it is a precious thing for studying. I have been looking for articles on Moebius' techniques for years and only today I was able to find yours.

I see that you are a skilled inker yourself, as obvious also from the analysis. May I ask you how did you train? Did you study/copy masters like Moebius or Duhrer?

I have recently switched from a Rapidograph to a nib, and I am trying to learn by drawing directly in ink AND by copying from masters like Moebius without first doing an underdrawing in pencil (I wonder if Moebius did use an underdrawing). This forces me to actually draw also when copying, to understand the form and the shape at the same time.

I am getting some results with this, but it will take a very long time before something decent comes out.

Thanks again!

Hello and thanks for reading … I hope to do more tech analyses and perhaps one day make a book of them, when time permits — which never seems to happen.

ReplyDeleteYes, I studied — and still study — Dürer and Moebius. Every move in crosshatching, Dürer did first, plus he really knew how to play the rhythm of line against the modeling, etc. Only w/ nibs do you get serious w/crosshatching, you get more line-flex and visual pop. Moebius sometimes skipped the pencilling or did very minimal pencilling. But as you've seen, he was a great draftsman and that's the key: knowing the forms and volumes so well mentally that the nib moves automatically in a precise rhythm.

I started as a technical inker and did x-hatching on the side till I got good enough to sell it. I used to practice by inking Old Master paintings, like, say, Grünewald. They shapes and volumes in many OM paintings are subliminally set up for x-hatching.

No substitute for practice and careful study … learn to look and also, learn to regard the white as important as the black when inking. Every single white shape, no matter the size, must have structural meaning.

Hello, thanks so much for your reply!

ReplyDeleteI am very happy to have found this blog and your art, a lot to learn and read. A book on the topic with the level of insight of your blog posts would be invaluable, in my opinion.

The idea of practice on inking Old Master paintings is just fabulous.

Thanks again!

Keep in touch, keep inking! Good luck

ReplyDeleteThanks!!!

DeleteP.S. About my previous post: I know it is DÜRER not Duhrer - Sorry! I need more sleep!